results

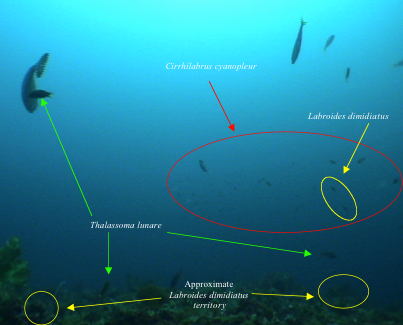

From our observations in 2005, we determined that a combination of the following attributes (figure 5) need to be in place for thresher sharks to visit a specific cleaning station on Monad Shoal at a predictable time:

• Presence of not less than two active cleaner wrasse territories

• Localised presence of not less than three individual moon wrasses

• Localised presence of an aggregation of blue-head fairy wrasse

-

• Clear behaviour indicative of cleaning interaction or posturing by

-

cleaner wrasse with various client species

• Clear behaviour indicative of cleaner posturing by moon wrasses

• Compressed mêlée of all of the above

These can be used to increase the probability of having a shark observation in situ.

how to find thresher sharks

© Simon P. Oliver, 2013

diver impact

temporal distribution

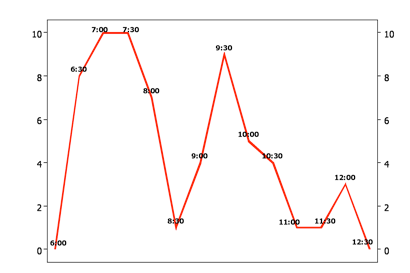

In an effort to test local opinion that thresher sharks visit Monad Shoal exclusively during early daylight hours, we developed a temporal distribution profile from our observations in 2005. Although the greatest number of thresher shark sightings take place during the first three hours of the dive day, the suggestion that presence only occurs between 6:00 and 9:00 o’clock, is not corroborated.

S

i

g

h

t

i

n

g

s

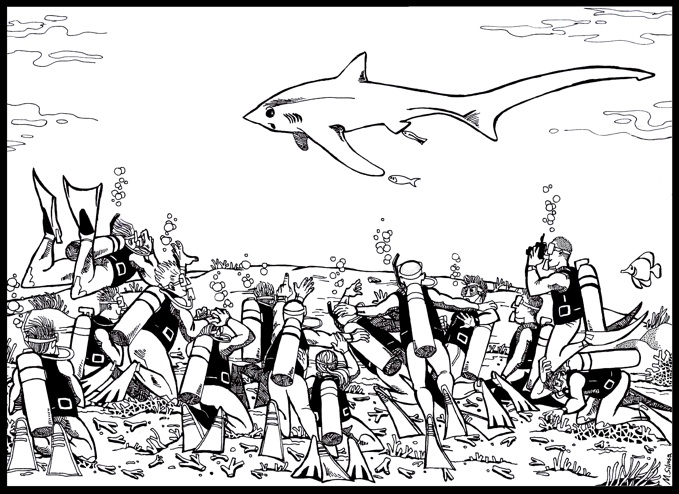

Figure 5: Attributes for predicting thresher shark presence on Monad Shoal. Two moon wrasse actively posture for clients while a third cleans a unicorn surgeonfish. An aggregation of blue-head fairy wrasse circulates over the drop off. Two pairs of cleaner wrasse from two separate territories invite clients.

Figure 1: Still grabs taken from Jonathan Bird’s “Blue World: The Shark with a Tall Tail” showing a boat captain dropping anchor on Monad Shoal. “Amazingly, the captain has anchored us within 50 feet of where we were yesterday. How does he do it!!??” says Jonathan on the second day of his thresher shark expedition on Monad Shoal.

Figure 2: Anchor damage to barrel sponges on Monad Shoal. Taken in July 2005, the photo on the left shows damage to a sponge which once hosted a thresher shark cleaning station. This site no longer exists. The photo of the sponge on the right was taken in July 2008. The yellow/orange colouration of the damaged spicules suggests that it recently suffered impact from an anchor.

Figure 3: Recreational divers trample the reef while waiting for thresher sharks and manta rays to show up at a cleaning station. During high season, the site is visited by hundreds of divers on a daily basis.

Figure 4: Diver interaction with pelagic marinelife. A professional photographer tramples the reef and perturbs the natural cleaning behaviour of a manta ray (left) and a thresher shark (right) on Monad Shoal.

We quantified significant habitat loss to the dived area of Monad Shoal (80 - 90%) and assessed that the pulverising effects of diver trampling is responsible for most of the rubble which characterises the site (figures 1 - 4). Additional damage has been caused by boats anchoring in spite of the clear presence of 5 marked buoys (figures 1 - 2). Overall not less than 2 of the 5 cleaning stations we established as ‘critical thresher shark habitat’ in 2005 have been completely eradicated by diver interference. To date, no evidence has been found to support claims that the area is currently, or has been recently, dynamite blasted. The natural behaviour of visiting elasmobranchs on Monad Shoal (thresher sharks, grey reefs, manta & devil rays) is perturbed by aberrant diver interaction (figure 4 ). Shark perturbance can be mitigated by using established site management and ‘respectful’ diver behaviour protocols.

objections

Our presence and work on Monad Shoal has been hugely supported and respected by government, the local community and the dive tourism industry. We have however received objections to our research from two of the dive shops on Malapascua Island. This is due to our observation that 80 - 90% of the dived area has suffered significant habitat loss to diver trampling. We are categorical in our view that site management protocols, beyond those proposed by the ‘Dive Shop Association of Malapascua’, are necessary to regenerate and protect the habitat that sustains thresher shark visit frequency. We are now working closely with the ‘Office of the Governor’ of Cebu to legislate more appropriate regulations at the state level.

What we have SHOWN so far

Anatomical cleaning distribution

We found significance in the number of times thresher sharks are cleaned in their pelvic zones.

behaviour

We described ‘Circle & Clean’ as a novel behavioural unit to elasmobranch ethology.

ethograms

We advanced the analysis of shark behaviour through the development of photographic ethograms and mapped thresher shark swim paths and interactions with cleaner fish to quantify behavioural trends.

Predictability

We developed a system to predict where and when thresher sharks are most likely to frequent.

cleaning stations

We characterised cleaning stations, cleaner fishes and thresher sharks in relation to each other.

Anthropogenic impact

We discovered that fisheries and the recreational dive tourism industries are both levying a significant impact on the sustainability of thresher shark populations. The former by long lining them for fins and meat, and the latter by allowing recreational divers to trample and pulverise critical reef habitat (film clip below).

Diver/shark interaction

We established that aberrant ‘disrespectful’ diving perturbs the natural behaviour of pelagic sharks and rays at Monad’s cleaning stations (picture mosaic below). Appropriate protocols to observe thresher sharks using SCUBA were developed and tested.